About

Biography

Rouzbeh Rashidi: Life, Cinema, and Philosophy of an Experimental Filmmaker

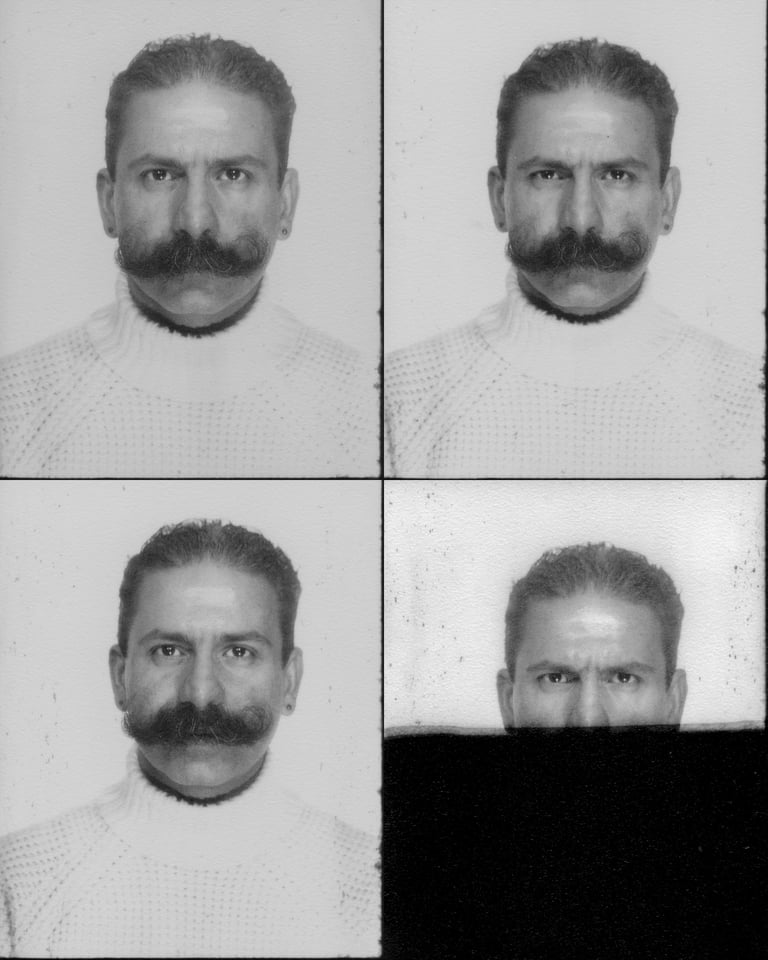

Rouzbeh Rashidi (born in Tehran in 1980) is an Iranian-Irish experimental filmmaker who has been making films since 2000, when he founded the Experimental Film Society (EFS) in Tehran. EFS began as a small collective devoted to avant-garde filmmaking apart from Iran's official film industry, and it became the seed of a prolific underground film movement. Rashidi relocated to Dublin in 2004, and EFS evolved into a Dublin-based international collective of "the most daring filmmakers" in Ireland. Over the past two decades, Rashidi has amassed an extensive body of work: by 2019, he had produced 11 feature-length films, all created entirely outside mainstream channels. Initially, he self-financed his projects, but later works received support from the Arts Council of Ireland, enabling him to continue pushing his experimental vision. His films have screened worldwide at festivals, museums, and galleries – from the Berlin International Film Festival to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tehran – reflecting the growing international recognition of his singular cinematic voice.

Significant milestones in Rashidi's career include the establishment of EFS (2000) and its development into a global network of experimental filmmakers, as well as the completion of an enormous ongoing project of personal film diaries called the Homo Sapiens Project (HSP). Through EFS, Rashidi has also curated and exchanged screenings globally, helping sustain an alternative micro-cinema circuit. In Ireland, he has become a central figure of the avant-garde film scene, mentoring younger colleagues and organising workshops and an EFS film school. This grass-roots institution-building parallels his artistic journey, underlining a commitment to an "entirely away from mainstream" mode of filmmaking that he has maintained since his Tehran beginnings.

Exile, Cinephilia, and Philosophical Influences

Rashidi's artistic identity is profoundly shaped by experiences of exile and by a deep engagement with film theory and philosophy. A key intellectual influence is the late French critic Serge Daney, whose writings explored how a cinephile's love of Cinema can originate from an absence or loss. Daney observed that passion for film often stems from "the emptiness created by the absence of a paternal role model," with the cinephile "like an orphan" seeking solace in the fantasy world of Cinema. Rashidi has explicitly cited this idea, expanding it to his own life circumstances. In his case, the sense of orphanhood was not only personal but also cultural: he grew up amid the upheavals of post-revolutionary Iran and later found himself a stranger in a new country. Thus, he notes that Daney's diagnosis is incomplete "without considering the absence of three other crucial elements: country, nation, and culture." When those pillars are missing, "the individual is compelled to create their own cinematic universe in order to thrive," turning Cinema into a substitute home. In other words, Rashidi's exile from his homeland and culture became the void that his cinephilia sought to fill. The act of filmmaking became for him a "dialectical journey" resulting in "the poetry of Cinema as a way of life."

Born and raised in Tehran during the tumultuous 1980s, Rashidi was directly affected by the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988) and the repressive atmosphere of the post-war Islamic Republic. He has described the eight-year war as a "gruelling ordeal" of his formative years, one whose trauma "simmer[s] beneath the surface" of his films. Rather than making overt war films, Rashidi channels these experiences in a veiled, symbolic manner – a creative choice that "has endowed his work and career with an enigmatic quality, teetering between clarity and mystery". As he puts it, "everything and nothing coexist" in his cinematic world, which oscillates between the real and the surreal. This oxymoronic description captures how memories of war and loss haunt his imagery without ever being explicitly spelt out.

Exile and dislocation are thus central themes that inform Rashidi's philosophical approach to Cinema. Having emigrated from Iran in his early twenties, he underwent the "tumultuous journey of immigration to Europe" and the "disorienting sense of being an outsider" in a new land. To navigate these challenges, Rashidi speaks of crafting a "fluid identity" for himself, one not bound to any single nationality. He initially refused to identify strictly as Iranian or Irish, instead "finding solace in being part of the world of Cinema and exile" itself. Cinema and exile became, in his words, "his true home." Every film he makes is thus "fueled by the 'agony' that resides within his life," the personal struggles and alienation transmuted into artistic expression. In this sense, his Cinema can be viewed as a sustained meditation on identity in between worlds. One scholar described his work as possessing an "eerie grittiness" that both "enraptures and estranges," reflecting the condition of exile – belonging everywhere and nowhere. Rashidi's heritage is from a "fractured ancient culture suspended between its past and future, devoid of any awareness of the present," and his films likewise often exist in a timeless, dreamlike register. By exploring his own liminal state, he touches on universal questions of home, memory, and identity.

Politically, Rashidi avows that "every film [he's] ever wanted to create has been political in the truest sense of the word," insofar as it reflects his personal encounters with societal forces. Yet he deliberately avoids overt political messaging or didacticism in his work. "Throughout his career, he has invariably transformed his artistic style and methodology" in response to political motivations, while… refraining from overtly addressing it within his films." In an ideal world, he muses, "films would be devoid of words, images, and sound" – a pure, universal experience unmarred by propaganda or even language. "Above all," Rashidi believes, "a film should not 'mean' but 'be.'" This striking dictum encapsulates his philosophical stance: Cinema's value lies not in delivering messages or clear-cut meanings, but in existing as an experience to encounter. Rather than conveying a direct social or political statement, Rashidi's films are the statement – a mode of being that implicitly contains his worldview. This approach aligns with a broader phenomenological view of Cinema. Rashidi is less interested in what a film is about than in how it is – how it feels, how it unfolds to the senses, how it phenomenologically engages the viewer. "In his films, the focus lies not on subject matters and meanings but on the impact and essence of events," he explains. It is the "hidden intensity" and emotional resonance of cinematic events "rather than the events themselves" that he aims to capture and transmit.

Accordingly, Rashidi invites the audience to interact with his Cinema on a sensory and intuitive level rather than through analytical interpretation. He has described his filmmaking as creating a kind of system or rhythm that the viewer "can travel through… creating a mental and physical response." He doesn't necessarily want the audience to "understand" a film intellectually so much as to "grasp it with their senses." In one interview, he cites experimental filmmaker Nathaniel Dorsky's distinction between a cinema that "depicts" human beings (theatrical storytelling) and one that "has all the qualities of being human" in itself – a form of cinematic poetry. Rashidi explicitly aligns with the latter, treating his films as organic forms with their own heartbeat and pulse, meant to be experienced phenomenologically. This is why his works often dispense with conventional plot and dialogue (which convey concrete information) in favour of mood, tone, and texture (which provoke experience). "Sometimes, even the creators may remain unsure of the visions they birthed," he notes, yet those visions "can profoundly evoke emotions and stir sensations within" the audience. In short, Rashidi's Cinema is to be felt before it is understood – a direct engagement of perception, much like encountering a painting or a piece of music.

Mysticism and metaphysics also inform Rashidi's framework. He describes his artistic practice in quasi-spiritual terms, suggesting that making films involves channelling forces beyond the self. His work is "deeply engaged with film history and primarily concerned with mysticism, philosophy, esotericism, cosmology, phenomenology, and hauntology." In conversation, Rashidi has likened himself to a medium or shaman. "I think of myself as a medium," he says, envisioning "a portal between the universes" through which he "transmits [s] energies" in the act of creation. Filmmaking for him is an almost alchemical or ritual act: "It is like I am having a séance when I am trying to trap images," he elaborates; "the art of filmmaking – any good cinema – captures ghosts or these entities quite well." In this poetic conception, the film director becomes a kind of sorcerer who conjures spectral impressions onto the screen. Rashidi's invocation of "ghosts" is not merely metaphorical. Many of his films feel haunted by invisible presences – whether the "specters" of lost homelands and memories, or the lingering echoes of old movies and genres. He frequently cites the "uncanny" nature of Cinema, noting that "cinema is all about ghosts and shadows" because once a film is finished and the moment of filming is gone, what remains is like a ghostly trace of reality, "behav[ing] as if it is alive" even though that moment in time is dead. This sensibility aligns with the concept of hauntology (a term coined by Jacques Derrida and popularised in film/cultural theory by Mark Fisher), which describes the way the persistence of the past haunts present culture. In Rashidi's case, his status as an exile and cinephile means he is constantly communing with absent things – the absent homeland, the absent past of Cinema – and making them present as phantoms in his work.

One striking example is Rashidi's use of landscape. Residing in Ireland, he became fascinated by the Irish landscape's "haunted (and wild) quality" and its layers of history. In his feature Phantom Islands (2018), he filmed on the west coast of Ireland using antiquated camera lenses to capture an otherworldly atmosphere. He intentionally employed 19th-century optical lenses – cumbersome antique photographic lenses – as a "self-imposed austerity" to create images that are "hazy, unfocused or cloudy". The result was a washed-out, hallucinatory visual style that evokes aged film footage or a decaying memory. "These are hard and difficult lenses," he admits, "but I had to find a way to really capture the enigmatic qualities of Ireland." By technically obscuring the image, Rashidi paradoxically makes the invisible (the atmosphere of mystery, the "ghosts" of the place) more palpable. An anthropologist who studied his work noted that Ireland, with its turbulent history, "is a country full of ghosts – literally and figuratively – and Rashidi explores this visually" in his Cinema. This hauntological approach – using the materials of Cinema (old lenses, decaying film/video formats, echoes of vintage film scenes) to manifest ghosts of the past – gives Rashidi's films a uniquely spectral character. It also connects to his mystic view of the filmmaker as someone who must "enter into [the] chaos" of uncontrollable forces and shape them via editing (a process he likens to channelling and controlling a magical ritual). Through this lens, one can see Rashidi's practice as cine-shamanism: summoning images from the limbo of memory, history, and imagination, and binding them into new cinematic forms.

Despite these esoteric dimensions, Rashidi's ultimate goal is not to mystify but to poeticise. He often refers to his work as "poetic cinema." "Without the ability to create poetry, what purpose does Cinema serve?" he asks pointedly. What he means by "poetry" is a cinema that favours ambiguity, emotion, and open interpretation – akin to how a poem evokes feelings and ideas without spelling them out. His films are unified by an "oneiric" (dreamlike) imagination and operate on a logic of images and sounds more than narrative. This places him firmly in the tradition of avant-garde poetic filmmakers (such as Stan Brakhage, Maya Deren, or Andrei Tarkovsky's more experimental side), for whom Cinema is akin to dreaming on film. Rashidi's recent works, in particular, embrace the form of the essay film or poetic documentary, blending personal reflection with observations of reality. For instance, Elpis (2023) is described as a "poetic essay film" that deals with war trauma and diaspora through sensory, non-linear techniques. It features an off-screen narrator (an Iraqi-German woman) reading a text about memory and loss, set against "lavish, ethereal landscapes" filmed across Europe. Rather than a straightforward documentary on the Iran–Iraq War, Elpis uses poetic association and haunting imagery to convey the feeling of exile and war's aftermath. This turn towards essayistic and documentary elements in his later career underscores Rashidi's constant search for new modes of expression: after nearly two decades of more cryptic experimental work, he began to directly confront the themes of war and diaspora that had long underlain his Cinema – but in his own idiosyncratic, poetic way. His cinematic philosophy thus synthesises many strands (cinephilia, phenomenology, mysticism, hauntology) into a singular aesthetic of exile: a cinema that is at once profoundly personal and open-ended, political in impulse yet poetic in form.

Filmography and Major Works

Rashidi's filmography is both prolific and varied. From 2000 up to 2019, he created eleven feature films (all of them resolutely experimental in nature) and an expansive series of shorts under the Homo Sapiens Project (HSP) banner. In the 2020s, he has continued to innovate, with new features like Elpis and Dreaming Is Not Sleeping bringing his total to 13 feature films by 2025. Below is a list of his major film works, including features and noteworthy projects:

Homo Sapiens Project (HSP) – ongoing project, 2000–present. An ever-expanding series of experimental video diaries and short films that Rashidi uses as a personal laboratory for cinematic exploration. HSP consists of hundreds of instalments (by 2021, he had made 201 HSP pieces), ranging from a few minutes to medium-length. These works are often silent or abstract, functioning as "enigmatic film diaries, "allowing Rashidi to test techniques and ideas. Many HSP pieces incorporate genre elements – he has "tried to dissect and analyse film genres, specifically horror and science fiction" within this series. The HSP project has strongly influenced his features; in fact, several feature films were developed directly out of HSP experiments. (One feature, HSP: There Is No Escape from the Terrors of the Mind (2013), even carries the HSP label in its title.) The HSP series is noted for its "undertones of science fiction, horror, the occult, and… post-apocalyptic" imagery. It also became a collaborative platform – Rashidi invited other international experimental filmmakers to contribute to HSP, making it a collective mosaic of "diverse poetics" in underground film. This culminated in HSP 201 (2021), an ambitious omnibus feature (~9 hours), imagined as a film made for both human and "extra-terrestrial" audiences. In summary, HSP is central to Rashidi's practice: it embodies his process of constant experimentation, and it feeds into his larger works.

Only Human (2009) – Rashidi's debut feature film. A zero-budget independent production, Only Human established his penchant for non-linear, poetic structure early on. (Details on this early film are sparse in published sources, but it marked the beginning of his feature output.)

Bipedality (2010) – A 67-minute experimental feature continuing Rashidi's exploration of human existence in an abstract style. Like many of his early works, it operates with minimal dialogue and a focus on mood and movement.

Closure of Catharsis (2011) – A 100-minute film notable for its minimalist setup: it reportedly consists mainly of a monologue delivered directly to the camera, shot in a single location. Rashidi has mentioned that this film was made "in response to [his] short involvement with the Remodernist Film movement", suggesting it was a turning point where he processed and moved beyond specific avant-garde influences. Closure of Catharsis exemplifies Rashidi's willingness to experiment with audience patience and narrative minimalism. It's essentially a film about the act of speaking and recording thought, pushing "anti-narrative" to an extreme.

2012 – Trilogy of Features: In 2012, Rashidi's productivity surged, and he released three feature-length works, each around 60–120 minutes :

Hades of Limbo (2012) – 81 mins.

Indwell Extinction of Hawks in Remoteness (2012) – 61 mins.

HE (2012) – 121 mins.

These films are fiercely experimental and diverse in form. Collectively, they continue to develop Rashidi's themes. HE, for instance, is described by Rashidi as part of a continuum leading into later films. These works draw on HSP experiments and delve into existential and metaphysical imagery. The very titles (evoking concepts of Hell, extinction, and an ambiguous pronoun "HE") point to their enigmatic, philosophical nature.

HSP: There Is No Escape from the Terrors of the Mind (2013) – 120 mins. This feature is a direct offshoot of the Homo Sapiens Project, effectively an HSP installment that grew into a full feature. It is emblematic of Rashidi's approach of "cannibalising" and reworking his earlier material: he has described how he would "re-ingest [his] older films, eviscerating and mutating them into HSP" – turning old footage into new creations. Terrors of the Mind is a oneiric, immersive experience that blurs reality (documentary-style scenes of people and places) with nightmares (distorted sound and images suggest horror). It can be seen as a bridge between Rashidi's early guerrilla filmmaking in Iran and his later Irish-set works.

Ten Years in the Sun (2015) – 148 mins. One of Rashidi's most acclaimed mid-career films, Ten Years in the Sun is an epic experimental feature that exemplifies his mature style. It is described as "an epic cinematic journey through mysterious landscapes and environments populated by enigmatic characters who move and speak as if under hypnosis." The film is constructed like a fragmented transmission or a series of vignettes: it feels "as if it has been created by an alien race in a language that we can follow and feel our way through but never fully comprehend", speaking to the viewer's senses rather than intellect. Indeed, critics noted that while the film lacks a conventional plot, it maintains an internal "rhythm that gives it a narrative momentum" and even a sense of resolution by the end. Throughout its lengthy runtime, Ten Years in the Sun weaves together elements of science fiction, B-movie horror, and detective-noir tropes – all abstracted into eerie, hypnotic sequences. For example, one might see visual nods to classic genre cinema (flickers of alien landscapes or shadowy conspiracies), yet the film never settles into one genre. This film also marked roughly a decade of Rashidi's feature filmmaking (the title perhaps alluding to his ten-year journey), and interviewers observed "a sense of completeness on one hand and the opening of new doors on the other" in it. In Rashidi's own reflection, Ten Years in the Sun (along with his next film Trailers) was a culmination of experiments, after which he would "turn a page" and begin a new chapter.

Trailers (2016) – 180 mins. An extraordinary 3-hour film, Trailers is perhaps Rashidi's boldest experiment in pushing the limits of narrative and form. It is pointedly without dialogue for its entire duration, relying purely on imagery and sound – a choice that induces a meditative, trance-like state in the viewer. Described as Rashidi's "latest, biggest and perhaps most ambitious feature" at the time, Trailers has been called an "opus" and an "ambitious epic". The film's ironic title belies its content: rather than a collection of coming attractions, it presents a cascade of scenes that function as "trailers" for imaginary films or parallel realities. The visual and sonic collage in Trailers is particularly intense – it mixes colour-saturated sequences, strobing lights, sudden shifts from near darkness to blinding brightness, and an array of sounds (from industrial noise to snippets of music). One reviewer noted the presence of "red glows, industrial noises, light on a woman's naked body… visions of depravity, static sounds of voices, noises à la Twin Peaks… Nightmarish pulsations, impending doom… Count to three, psychedelic vibrant glows… Lost Highway meets Blue Velvet" in the tapestry of Trailers. The film is rich in intertextual film references – Rashidi, a true cinephile, nods to everything from surrealist horror to erotic arthouse to Lynchian thriller. Yet, as chaotic or disjointed as it may seem, Trailers does have an internal structure guiding it. Its opening title reads "a spectacular attraction by Rouzbeh Rashidi, Pictures of a far-off world," signalling the viewer to treat the film as a kind of cinematic theme park or hallucinatory journey. Critics have remarked that watching Trailers is like experiencing "lucid dreaming", where images "jumbled out of order" still evoke emotional continuity. The film was also an opportunity for Rashidi to play with his love of Cinema's past explicitly: for instance, Trailers incorporates an experimental music album (Cinema Cyanide) made by EFS, which remixes sounds from earlier EFS films into new soundscapes. This self-referential aspect – reusing and recontextualising material – is a hallmark of Rashidi's practice, reflecting his idea that "nothing goes to waste" and old footage can be "rediscovered as found footage" in new works.

Phantom Islands (2018) – 86 mins. One of Rashidi's most visually poetic films, Phantom Islands, is set on the Irish seacoast. It follows a couple (played by experimental filmmakers Daniel Fawcett and Clara Pais) as they wander through windswept islands and shores. The film is a loose narrative of a relationship in crisis, but it is told in a hallucinatory, fragmentary manner. A critic drew parallels between Phantom Islands and Michelangelo Antonioni's existential landscapes – characters serving as "figures of ambient feeling" amid a scenery that reflects their inner void. Indeed, Rashidi's two protagonists in Phantom Islands appear as "abstractions of emotion on the verge of disintegration". The imagery – tinted in pale blues and grays – and the persistent sound of wind and waves create a sense of both presence and absence. Rashidi gives the well-touristed Irish coast "a new lease of life", rendering it ominous and "pulsating" with "intrigue and despair." There is very little dialogue; instead, the film's power comes from the "ever ringing void of muted language" and the isolation of the couple in the vast landscape. The title Phantom Islands itself hints at hauntology: these are islands of the mind as much as real places, "phantoms" in that the film blurs reality and illusion. Rashidi has stated, "As an experimental filmmaker, I'm naturally drawn towards the overlaps between documentary and experimental cinema." In Phantom Islands, one can see this overlap clearly – the scenery and the couple are fundamental (documentary elements), but their presentation is surreal (experimental form). The film invites multiple interpretations (are the characters real or ghosts? Is this a memory, a myth, or a literal trip?) while immersing the audience in a hypnotic audio-visual experience. This work premiered at the 2018 Dublin International Film Festival and earned praise for its bold form.

Luminous Void: Docudrama (2019) – 71 mins. This feature is a hybrid of documentary and fiction, reflecting on Rashidi's own cinematic milieu. Co-produced by EFS, Luminous Void: Docudrama is meta-cinema: it is about the Experimental Film Society and the creative philosophies of its members, including Rashidi. The film's title, "Luminous Void," echoes the name of a book (Luminous Void, published in 2017) on EFS filmmakers, suggesting a self-referential intent. True to its "docudrama" label, the film interweaves candid footage, staged scenes, and voice-overs by various artists. One description notes that Luminous Void unleashes "a parade of visionary scenes" in an ornate visual style. It begins with an arresting, vibrant sequence that one commentator compared to the opening of Peter Greenaway's A Zed and Two Noughts, fused with the swirling, disorienting music of a Michael Nyman or Bernard Herrmann score. The film features Rashidi himself on screen (unusual, since he typically stays behind the camera) alongside other EFS collaborators, and at times they appear in a car with rear-projected landscapes, discussing or musing in voice-over about Cinema and the end of the world. The audio includes "echoing voices which philosophise about the world's end", giving the piece an apocalyptic, reflective tone. As the film progresses, it becomes increasingly abstract and layered: images flicker like old celluloid, bodies appear and disappear, and three women recur as enigmatic figures – described as "the witches of the damned, the angels of tomorrow's dream" – who laugh and taunt wordlessly at the camera. Luminous Void: Docudrama can be seen as both a summary of Rashidi's first two decades of work and a last flourish of his earlier style before transitioning into his next phase. By ending the 2010s with a self-reflexive docu-fiction, Rashidi effectively closed a chapter, examining the "luminous void" where his art resides: a place between reality and imagination, individual vision and collective filmmaking. (Notably, Luminous Void and Rashidi's other works around this time were recognised by scholars; for example, a comprehensive academic history of the Remodernist film movement in 2019 gave attention to Rashidi's oeuvre.)

Elpis (2023) – 71 mins . Elpis marks a new direction in Rashidi's filmography, inaugurating what he calls a fresh phase exploring "slow cinema, poetic documentary techniques, and film essays." The title comes from Greek mythology (Elpis is the spirit of hope left in Pandora's box) – an apt reference for a film about hope and despair in the aftermath of war. In Elpis, for the first time, Rashidi squarely addresses the Iran–Iraq War and its psychological impact on those who, like him, grew up under its shadow. The film is described as "a poetic essay film about the effects of the Iran–Iraq War and its trauma and psychological impact," told through the narration of a woman writing a book. That narrator, voiced by German-Iraqi writer Claudia Basrawi, reads a first-person text (in English) reflecting on war, diaspora, love, alienation, and displacement. Visually, Elpis spans multiple countries: it showcases "lavish, ethereal landscapes" of Estonia, Latvia, Ireland, and Germany – all places tied to themes of conflict or exile (e.g. the Baltic sites of past wars, Ireland's emigrant history, Germany as home to many exiles). The juxtaposition of Basrawi's personal, introspective narration with these grand natural landscapes creates a meditative tone. Rashidi uses Elpis to fuse his autobiographical subtext with a more outward-looking, documentary style – yet the execution remains firmly poetic and experimental. The director's statement accompanying Elpis reiterates the Daney-inspired philosophy behind his work (Cinema as an orphan's refuge in the absence of homeland). It emphasises that the "essence" of his filmography lies in "the profound impact of war on [his] formative years," albeit "veiled" beneath enigmatic imagery. Thus, Elpis brings to the surface what had long been hidden in his films in an essayistic, reflective register. The film premiered in 2023 and was quickly recognised as a significant evolution for Rashidi – one commentator called it the beginning of a "spiritually transformative path" that continues in his next film.

Dreaming Is Not Sleeping (2025) – 64 mins. Rashidi's newest feature at the time of writing, this film continues the essay film format introduced in Elpis. Dreaming Is Not Sleeping is described as "an introspective essay film exploring the relationship between memory, existence, and time, narrated by a spectral voice drifting through ancient ruins." The film's narrator – referred to as a "spectral voice" – guides the viewer through decaying historical sites, philosophising about perception and time. The synopsis indicates that the work "contemplates perception, clairvoyance, and whether the present can be seen through the lens of memory, blurring the lines between past, present, and future." This suggests Dreaming Is Not Sleeping deepens Rashidi's engagement with temporal hauntology: it features a ghost-like speaker and ancient ruins (symbols of the past), and its narrative structure is "deliberately fragmented, mirroring the non-linear nature of dreams and memories." In the director's statement, Rashidi calls the film "a poetic meditation on the nature of human existence, perception, and the creative process itself," and he describes his approach to film here as "a form of clairvoyance" – again invoking mystical terms. By challenging viewers "to question the very essence of perception," he blurs reality and imagination, creating "a dreamlike state where time becomes fluid and malleable." All these aspects show Rashidi further integrating his philosophical preoccupations (memory, time, mortality) into the very form of his Cinema. Dreaming Is Not Sleeping has been noted as a "natural continuation" of the path started with Elpis, pushing even more towards a transcendental, spiritual cinematic experience.

This list by no means covers all of Rashidi's output (he has numerous short films as part of the Homo Sapiens Project, collaborations, and side projects), but it highlights the major works and the evolution of his art. From the early no-budget features in Tehran to the recent essay films shot across Europe, Rashidi's filmography reflects a relentless experimentation and a deepening engagement with the personal/philosophical themes of exile, memory, and cinematic ontology.

Artistic Techniques and Style

Rashidi's creative process is marked by an exploratory use of film technology and a deliberate break with traditional narrative Cinema. He is known for employing an unusually diverse array of imaging equipment and formats, from the latest digital cameras to obsolete analogue devices. According to his own accounts, he has made "bold use of a wide range of moving image devices, including camcorders, digital cinema cameras, DSLR cameras, mirrorless cameras, drones and aerial imaging equipment, action cameras, consumer camcorders, surveillance video systems, telescopes, spotting scopes, night and thermal vision devices, analog video… and Super 8 film." In practice, this means Rashidi chooses the tools of filmmaking based on the particular texture or aesthetic he wants for each project. For example, some of his HSP diary films were shot on grainy VHS or low-fi video for a raw, intimate feel; by contrast, Elpis and Dreaming Is Not Sleeping were captured in high-resolution 8K digital, allowing for sweeping detail of landscapes. This chameleon-like approach to format stems from Rashidi's belief that no technology is off-limits or superior – "I respect and enjoy working with all the formats and use them according to the specific project… A clever filmmaker will never restrict herself or himself," he said, criticising the false dichotomy of film vs. digital. In line with this, he "despises" debates over medium purity and instead exploits whatever cameras are available, even DIY techniques, to serve his vision.

One distinctive hallmark of Rashidi's visual style is his experimentation with lenses and optics. As noted, he has gained attention for using antique 19th-century lenses in some films. These specialist lenses (such as old portrait lenses from the 1800s) lack the crisp clarity of modern glass; instead, they produce images with soft edges, swirling bokeh, and occasional distortions. Rashidi employs them to achieve a unique "pictorialism aesthetic," enveloping his images in a kind of patina or haze that evokes early photography. The soft focus and vignetting of these lenses contribute to the oneiric (dreamy) quality of his visuals. They also literalise the theme of seeing the present through the lens of the past – as if we are watching contemporary footage through an old, clouded window. Beyond antique lenses, Rashidi is constantly tinkering with visual effects in-camera: he has been known to attach prisms, filters, or even handmade lens modifications to create flares and abstractions. As a skilled still photographer himself, he "fearlessly explores uncharted territory by experimenting with unconventional lenses and filters, even crafting his own." This hands-on manipulation of the image at the optical level is part of Rashidi's craftsmanship, aligning with his admiration of directors like Fritz Lang, who saw themselves as "craftsmen" of Cinema.

In the sound design of his films, Rashidi likewise takes an innovative and often non-traditional approach. Dialogue is sparse or entirely absent in many of his works. This is a conscious choice to break away from the word-driven logic of conventional film and to hark back to the silent cinema era. He "consciously avoid[s] conventional dialogue in most of his works," paying homage to the early days of Cinema" when stories were told purely through image and music. By minimising speech, Rashidi encourages viewers to read the film through its visuals and sonic atmosphere instead of through the characters' verbal explanations. In place of dialogue, he meticulously constructs ambient soundscapes. Natural sounds (wind, water, echoing footsteps) are often amplified to a hyper-real level, creating an immersive aural environment. At times, jarring sound effects or bursts of noise will rupture the calm – in Trailers, for example, sudden "static sounds of voices" and hums punctuate the soundtrack, contributing to a sense of disorientation. Music is another key component: Rashidi frequently collaborates with experimental musicians, including those within EFS. The collective's music project Cinema Cyanide contributes to some films by remixing audio from prior films into new musical pieces. The result is a kind of self-referential musical layering that complements Rashidi's visual collage. In Luminous Void: Docudrama, we hear overlapping voices and a dense mix of musical cues (from classical to electronic), all used not to guide a narrative arc but to evoke an emotional, almost subconscious resonance. This sound design style aligns with Rashidi's poetic, phenomenological aims: sound is not subordinate to dialogue or plot, but rather an equal partner to the image in creating mood and meaning.

The editing and narrative structure of Rashidi's films are deliberately unorthodox. He often adopts a montage-driven approach that privileges association and rhythm over continuity. Rashidi has described his process as trying to reach a "ground zero of drama through the systematic removal and breaking down of any narrative structures." In practical terms, this means he will excise exposition, backstory, and sometimes even obvious cause-and-effect sequences, in order to create a purer audio-visual experience. Many of his films consist of vignettes or episodes held together by thematic or tonal unity, rather than a plotted storyline. However, this does not imply chaos; Rashidi is very much concerned with the form and flow of his films. Critics and interviewers have noted that even in the absence of a conventional plot, his features possess "tangible structure and precise rhythm" that give a sense of forward momentum. Rashidi himself often compares his structuring method to musical composition. "Creating cinema with rhythm by structuring, juxtaposing, pacing, lights, shadows, flicker, sound and all the rest" is how he defines his editing approach. He designs his films almost like symphonies or visual music pieces, where each sequence is a motif that builds and contrasts with others. "There is always a sense of some logical progression of sound, images and emotions, just like a symphony," he explains. This musicality is evident in the way sequences often crescendo to an intense pitch (e.g. a frenzy of quick cuts and loud sound) and then decrescendo into quieter, slow-paced moments of long takes and near silence. Such modulation keeps viewers engaged at a sensory level. It also reinforces that Rashidi's films are experiential journeys; one does not watch them for a story pay-off, but rather to be carried through a series of emotional and perceptual states.

To achieve this, Rashidi employs a range of editing techniques: rapid montage (inherited from Soviet and avant-garde traditions), slow fades and superimpositions (often producing ghostly overlaps of images), and deliberate non-linear sequencing. For instance, Trailers by design feels like reels of film spliced in random order, yet it creates its own surreal narrative through recurring symbols (red lights, forest scenes, faces appearing then melting away). In Phantom Islands, the editing toggles between moments of almost documentary stillness and sudden bursts of hallucinatory montage, mirroring the mental state of the characters. Rashidi is also unafraid of testing the viewer's endurance – he will hold on long takes well past the point of conventional "interest," creating a meditative or hypnotic effect. This aligns him with the ethos of slow Cinema, a movement defined by long duration shots and minimalistic action, aiming to sharpen the viewer's awareness of time. Rashidi's recent films, Elpis and Dreaming Is Not Sleeping, adopt this slow-cinema pacing to a degree, with protracted contemplative scenes and voice-over guiding the reflection.

Visually, Rashidi's mise-en-scène often features stark, striking imagery and a fascination with the act of looking. A recurrent motif is the camera/eye itself: characters in his films are sometimes shown filming or photographing (a reflexive nod to the act of image-making), and there are numerous shots of eyes, mirrors, and lenses. The Ruptured Ambience essay observes that across films like Trailers, Phantom Islands, and Luminous Void, Rashidi populates his frames with "visual optics galore" – scenes of people looking through cameras, or cameras gazing at bodies – as if commenting on the very process of capturing images. Another motif is the human body, often depicted in vulnerable or symbolic ways (e.g. unclothed figures in nature, suggesting a return to a primal state). He doesn't shy away from nudity or intimacy, but these elements are presented in an artfully detached manner, more "abstractions of the conscious mind" than erotic scenes. The colour palette of Rashidi's films ranges from the washed-out monochromes of Phantom Islands to the saturated neon hues in parts of Trailers and Ten Years in the Sun. This variability again shows his project-by-project approach: each film creates its own visual universe.

In terms of genre, Rashidi's work is difficult to classify, but he often references genre cinema in oblique ways. He has a well-documented love of horror and science fiction – genres he considers rich for experimentation – and he frequently incorporates their iconography (though fragmented and decontextualised). For instance, Ten Years in the Sun contains what feels like sci-fi "props" (strange scientific devices, hints of aliens or conspiracies) and horror "atmosphere" (eerie sound design, unsettling behaviours) without ever coalescing into a conventional sci-fi or horror plot. This method of genre deconstruction might be compared to the practices of directors like David Lynch or the Quay Brothers, but Rashidi's approach is more radical in stripping out narrative. He has said he wants to "submerge [genres] totally into an experimental cinema" and "push these ideas to their extreme limits until the form itself begins to break down." In effect, he abstracts genre elements into pure mood or spectacle. This is evident in Trailers, which feels like one giant homage to the sensory impact of genre cinema – from giallo-like flashes of colour to noirish shadows to apocalyptic sci-fi imagery – all cut free from their story moorings, leaving only the affective core. Rashidi's cinephilia means that one might catch homages: for example, critics saw echoes of Ingmar Bergman's intense close-ups and Jean-Luc Godard's colour flashes in his films. Rashidi himself has cited Godard and Bergman among his favourites, alongside figures like John Cassavetes, and one can find traces of each (Godard's fragmentary editing, Bergman's existential starkness, Cassavetes' raw intimacy) in the patchwork of his style. But ultimately, Rashidi recombines these influences into something quite singular – an idiosyncratic film language that is immediately identifiable as his own.

In summary, Rashidi's artistic techniques are characterised by experimentation at every level: image capture (using all formats and odd lenses), sound design (eschewing dialogue for atmospheres), and editing (creating non-linear, musical structures). He resists conventional storytelling, yet his films are carefully constructed to provide a coherent emotional and sensory journey. This maverick style places him at the forefront of contemporary experimental filmmaking, where pushing the boundaries of form is essential. As a result, his oeuvre consistently challenges viewers' perceptions of what Cinema can be – not a medium of clear stories or messages, but, as he says, "a journey of exploration and self-expression" in its own right.

Theoretical Contexts and Influence

Rouzbeh Rashidi's work can be situated within several broader movements and contexts in film art. He is often associated with the Remodernist film movement, the international revivalist movement that emerged in the early 2000s as a reaction against postmodern irony in art. Remodernist film, informed by the Remodernist manifesto in painting and spearheaded by a group of underground filmmakers, called for a return to spirituality, sincerity, and emotional truth in Cinema. Rashidi was indeed connected with this movement: he has been cited as "one of the most prominent figures of the Remodernist Film movement, which emerged at the beginning of the 21st century." His films from the late 2000s and early 2010s – with their raw earnestness, low-budget aesthetic, and rejection of mainstream conventions – exemplify the Remodernist ethos. For example, Remodernist filmmakers championed personal expression over technical polish, something clearly visible in Rashidi's early DIY works. Additionally, the Remodernist emphasis on the transcendent or spiritual aspect of art aligns with Rashidi's mystical/philosophical concerns (e.g. "cosmology, esotericism, hauntology" in his themes ). However, while he was influenced by the movement, Rashidi did not remain confined to it. He notes that Closure of Catharsis (2011) was made after a brief involvement with Remodernist film, perhaps signalling his stepping away from any formal manifesto to carve his own path. Still, the association remains in critical discourse: his wildly experimental, "magical realist" imagery and oneiric style have been "associated with the Remodernist movement." Scholarly research on Remodernist film has indeed covered his work. In a sense, Rashidi personifies the Remodernist ideal of the artist as outsider: an uncompromising filmmaker pursuing a "dreamlike" cinematic experience with "idiosyncratic methods", as noted in his biography.

Beyond Remodernism, Rashidi's practice belongs to the long lineage of the avant-garde and underground Cinema. His refusal of commercial storytelling, his embrace of abstraction, and his collaborative collective (EFS) all hearken back to earlier waves of experimental film. One can draw parallels between EFS and movements like the No-Wave Cinema of the 1970s–80s in New York, or the coop movements in Europe – filmmakers banding together to share resources and exhibit outside traditional venues. Rashidi's emphasis on the materiality of film (using different formats, showing the grain of analogue video, etc.) recalls the Structural film filmmakers of the 1960s who foregrounded the film medium itself. Yet, unlike strict structuralists, Rashidi is not devoid of content – he brings in personal and emotional dimensions. In this blending of formal experiment with subjective expression, he could be compared to someone like Stan Brakhage (who merged abstract imagery with personal vision) or Chris Marker (who made essay films that are philosophically rich and visually unorthodox). Indeed, Rashidi's turn to essay film in Elpis and Dreaming Is Not Sleeping places him in dialogue with the poetic documentary/essay film tradition, exemplified by filmmakers like Marker, Agnes Varda, or Patrick Keiller – artists who blur the boundary between documentary fact and poetic introspection. Rashidi's essays are distinctive in that they maintain a strong experimental edge (he is less linear and more opaque than most essayists). Still, they share the goal of using Cinema as a medium of thought, not just storytelling.

Another context is the influence of the Slow Cinema movement of the 2000s (filmmakers such as Béla Tarr, Tsai Ming-liang, Chantal Akerman, etc., known for long, slow takes and minimalism). While Rashidi's earlier work is often frenetic and montage-heavy, his later shift (with Elpis) towards slower pacing and meditative tone indicates an affinity with slow cinema aesthetics. In Elpis, for instance, he allows the camera to linger on landscapes and utilises silence and stillness in a way that evokes slow Cinema's contemplative approach to time. This is an interesting evolution: after "breaking" narrative Cinema into fragments with films like Trailers, Rashidi seems interested in exploring duration and contemplation, suggesting a synthesis of slow Cinema's patience with his own hauntological imagery. By combining these, Rashidi contributes a unique voice to slow Cinema – one inflected with surrealism and archival ghostliness that isn't common in that movement.

Crucially, Rashidi's work underscores the idea of Expanded Cinema – not necessarily in the sense of multi-projector performances, but in the broader sense of expanding what Cinema encompasses. He treats Cinema as more than just films on a screen: it's a way of life, a philosophy, a community practice. His activities with EFS (screenings in alternative spaces, online Vimeo on-demand distribution, published writings, workshops, etc.) demonstrate a conception of Cinema as an ever-evolving, collective art form. As his biography notes, for Rashidi, "Cinema is an ever-evolving art form, constantly being invented and reinvented." This echoes the credo of 1970s Expanded Cinema exponents (Gene Youngblood, etc.) who saw the future of Cinema in new technologies and new artistic integrations. Rashidi's integration of the internet and social media for networking is one practical extension – by leveraging platforms like Facebook, he built a fan base of tens of thousands for EFS, using digital connectivity to sustain experimental film distribution. Similarly, his willingness to incorporate any available media (from cell-phone video to 8K footage) into his projects reflects an expansiveness of vision. In spirit, Rashidi stands for an expanded definition of filmmaking: not constrained by format, length (he's made everything from one-minute pieces to nineteen-hour epics), or exhibition context (gallery, Cinema, online, all are possible). This positions him as a contemporary embodiment of "cinema reinvented."

Rashidi's theoretical and aesthetic contributions have also been recognised academically and critically. Critics often point out the rich intertextual nature of his work – how it converses with film history. For instance, in discussing Phantom Islands, references were made to Antonioni, Bergman, and others to situate Rashidi's approach to using landscape and silence. In Trailers, viewers noted homages to various cult films and genres. Rather than derivation, these allusions function as a kind of cinematic hauntology, with Rashidi allowing the "ghosts" of Cinema's past to live on in new forms. This has endeared him to a subset of cinephiles who revel in deep-cut references and the sense of film history being memory. It also means that his films reward repeat viewings and study, as one might unpack layer upon layer of meaning and reference. As a result, his work has been written about in film journals, cultural anthropology essays, and scholarly dissertations, highlighting its relevance to discussions of cinephilia, memory, and identity in contemporary art.

Finally, culturally, Rashidi serves as a bridge between Iranian and Irish avant-garde Cinema, two scenes not often linked. In Iran, experimental filmmaking has existed (e.g. the films of Kamran Shirdel or the video art of Shirin Neshat), but Rashidi's generation had limited infrastructure for non-narrative Cinema. By founding EFS in Tehran, he took an unusual initiative. His subsequent success in Ireland (where he's now considered an Irish experimental filmmaker as well) makes him a case of transnational art. He brings a specific Persian sensibility – one could argue that the mysticism and poetry in his work draw on Iranian artistic traditions (Sufi mystic poetry, etc.) – into an Irish context, while also injecting European art cinema with influences from Iranian culture and history (like the war). This cross-pollination enriches both contexts. His personal story of exile and artistic self-creation also exemplifies the positive side of diaspora: that an artist can carry a cultural heritage within them and express it in new forms abroad. Rashidi has said that to cope with displacement, he adopted Cinema as his culture – effectively turning the medium into his nationality. In doing so, he has become a cosmopolitan figure whose work resonates with anyone who has felt unanchored or "in-between." Given the global refugee and migration crises of recent decades, Rashidi's Cinema of Exile may also gain broader pertinence as an artistic reflection of those experiences.

Rouzbeh Rashidi's journey from Tehran to Dublin and central Europe, from outsider cinephile to leading experimental filmmaker, is a testament to how Cinema can become a vessel for philosophy and personal history. He has meticulously crafted a poetic, phenomenological cinema that challenges spectators to rethink what a film can do. In Rashidi's films, narrative is shattered and reassembled into evocative fragments; images are treated as living beings or ghosts; sound is a texture that envelops rather than a mere accompaniment. Drawing on influences as disparate as Serge Daney's theories of cinephilia, the mystical symbolism of ancient cultures, and the visceral shocks of horror cinema, Rashidi has synthesised an artistic style that is uniquely his own. His work embodies a delicate balance between mystery and clarity: it resists straightforward interpretation, yet its emotional or sensory impact is unmistakable. This balance is perhaps what he means by having "everything and nothing coexist" on screen – a simultaneity of meaning and void that the viewer must navigate.

As a filmmaker-tutor, Rashidi has contributed significantly to contemporary film art. He keeps alive the flame of the avant-garde in an age dominated by commercial media, proving that cinematic language still has new frontiers. His films can be seen as open texts or "partial truths" – incomplete in the best sense, inviting audiences to bring their own imagination to complete the experience. And while steeped in personal and cultural memory, they transcend the personal to touch on universal themes of memory, time, exile, and the very nature of reality. In the context of a book on experimental filmmaking and philosophy, Rashidi stands out as an artist who doesn't just make films but thinks through film. His Cinema asks fundamental questions: What does it mean to see? Can images capture the unseen (the spiritual, the traumatic, the absent)? How does one's identity shape the art one creates, and vice versa? Each Rouzbeh Rashidi film is, in effect, a meditation on these questions – a fragment of a continuously evolving cinematic philosophy.

In one of his reflections, Rashidi imagines "a film that would tune into mysterious signals" – like finding a strange frequency on a radio, full of unknown languages and sounds. This is an apt metaphor for his own oeuvre. He tunes Cinema to frequencies that are not commonly heard, transmitting signals from his interior world (and perhaps from some collective unconscious) to anyone willing to listen and watch. For those open to it, engaging with Rashidi's work can be a transformative experience, akin to that "séance" he describes – communing with ghosts, memories, and dreams through the medium of light and sound. In the ever-continuing discourse of experimental film, Rouzbeh Rashidi has carved out a vital chapter that exemplifies how film can be modern and ancient, personal and cosmic, rebellious and poetic all at once. His films do not mean – they are, and in their being, they quietly expand the possibilities of Cinema and one's psyche.

Feature Films

Since the year 2000, he has devoted his attention to creating and overseeing the development of 13 innovative feature-length films. Initially, he provided full financial support for his early films, while his more recent works have been low-budget productions supported by the Arts Council of Ireland. The complete filmography is HERE

Home Sapiens Project (HSP)

The Homo Sapiens Project, an experimental video series, is the brainchild of Rouzbeh Rashidi. From its humble beginnings as enigmatic film diaries, the series has been evolving over time to refine its craftwork form into feature films. During the Project’s journey, Rashidi has had the opportunity to explore and embrace various experiences while always staying close to the core components of the project — compelling renderings of both people and places imbued with undertones of science fiction, horror, the occult, and associations to post-apocalyptic rituals and dystopian settings. Rashidi has sought out prestigious global contributors, both behind and in front of the camera, to help create and assemble diverse poetics of instalments varying in length and scale.

Screenings and International Exposure

Films have been exhibited worldwide at film festivals, museums, galleries, and cultural institutions, including the 70th Berlin International Film Festival, Spectacle Theater in New York, Festival du Nouveau Cinéma in Canada, Fronteira Film Festival in Brazil, Bogotá Experimental Film Festival in Colombia, Museum of Modern Art in Brazil, Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, Sharjah Art Foundation in the UAE, Istanbul International Experimental Film Festival, European Film Festival in Romania, Dublin International Film Festival, Cork Film Centre Gallery, Cork Film Festival, Lausanne Underground Film & Music Festival in Switzerland, Film Development Council of the Philippines, Irish Film Institute, Cinemateca Nacional del Ecuador, and Onion City Experimental Film & Video Festival in the USA. These films have been screened on every continent except Antarctica. Details are HERE

Funding Awards

Rashidi is a recipient of the Film Bursary Award, Film Project Award, and Next Generation Artist Award from The Arts Council / An Chomhairle Ealaíon. He has also received awards and support from Culture Ireland, Dublin City Council, Fingal County Council Arts Office, and Temple Bar Gallery and Studios.

International Recognition

2023 Special mention in the “STUDENT JURY AWARD” category at the Flight / Mostra Internazionale del Cinema di Genova

2023 Oberhausen Seminar (69th International Short Film Festival Oberhausen)

2020 Berlinale Talents (70th Berlin International Film Festival)

2018 Best Feature-length Experimental Film, Istanbul International Experimental Film Festival.

2017 Festival de Diseño Audivisual Experimental de Valdivia (EFS Award)

2009 Best Short Film, 3 SMEDIAS AWARDS.

2008 Best Short Film, Cork Youth International Film Festival

International Film Festival Jury Panels

2024 Tirana International Film Festival (Albania)

2021 Kinoskop - Festival analognog filma (Serbia)

2020 Berlin Revolution Film Festival (Germany)

2018 Experimental Film Festival Process (Latvia)

2017 Bogotá Experimental Film Festival (Colombia)

Residencies

2021 Lichtenberg Studios (Berlin-Germany)

2017 Tyrone Guthrie Centre (Monaghan-Ireland)

2016 Lichtenberg Studios (Berlin-Germany)

2015 Lichtenberg Studios (Berlin-Germany)

2012 The Guesthouse (Cork-Ireland)

2011 The Guesthouse (Cork-Ireland)

Academic Research

His work has been the subject of much academic research, including the Remodernist film movement’s first comprehensive history by Florian Maricourt at the Université de la Sorbonne Nouvelle, under the research direction of Nicole Brenez, a professor of cinema studies at the Sorbonne and curator of the avant-garde film series at the Cinémathèque Française in Paris. Read it HERE (in French).